Results of the 2022 elections, the coup attempt, and the challenges facing the working class in order to defeat the neofascist ongoing insurrection – Editors

It is clear from the results of the federal legislative elections that the left (lato sensu) lacks even a sufficient number of congressional representatives (one third) to avoid an impeachment process against newly elected President Luis Ignacio “Lula” da Silva. This makes the government hostage to the right, not only for approving any measure by a majority, but even to remain in power. This is even more the case when it has a neoliberal vice president who has the same vision of economic policy that the bourgeoisie and the mainstream media support.

In the case of the executive branch, as we know, Lula won in the second round (about the first round see Natalia de Oliveira’s article) only by a very narrow margin: Lula da Silva with 50.9% (60,345,999 votes) and Jair Bolsonaro 49.1% (58,206,354 votes). As expected, Bolsonaro did not recognize his defeat. But seeing himself, as he said, without the necessary military support to stay in power, he fled to the United States. He left behind with his Minister of Justice a decree, bearing his name but without a signature, stating that he would not accept the election results and would intervene with the Electoral Court.

His supporters formed camps in Brasilia to call for a military coup against Lula. These encampments were set up on the grounds of army headquarters, which collaborated with them, even providing energy and other infrastructure. On December 24th, members of these camps placed an explosive device underneath a fuel truck at the Brasilia Airport, but it was discovered in time. In the early days of January, in a very well-funded operation, hundreds of buses arrived in Brasilia to join the encampments.

Lula’s Minister of Justice and the Minister of Defense knew about it. They also knew that the governor of the Federal District and his Secretary of Security (precisely Bolsonaro’s former Minister) had ordered the removal of the fences protecting the Presidential Palace. At the time, Lula’s Minister questioned the Secretary and the Governor, who told him, however, that everything was under control and that nothing would happen. Thus, the government, deceived like a naive child, did not take any additional security measures. (Lula wasn’t even in town.)

Such are the basic facts regarding the Brazilian version of the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. In Brazil the attack was actually even worse, because it counted not only on inaction but also support from the armed forces, which prevented part of the police from acting. It was also more serious than January 6 because all the three branches of the State were attacked. Lula’s own presidential guard and institutional security did nothing and even had their weapons taken by the neo-fascist mob which, as planned beforehand in WhatsApp groups, sacked the Parliament, the Supreme Court, and the office of the Presidency, including the ministerial offices and that of the First Lady.

Demonstrating a total lack of control by the military apparatus, the leisurely exit of the neo-fascist bandits lasted about three hours. Many, supported by the army, returned to their camps and homes. Lula’s response was limited to a federal intervention under the auspices of the Federal District police. He did nothing about the armed forces, except to remove from his guard and from the palace part of the military officers that should have taken steps to prevent the coup attempt.

Incredibly, only a right-winger, Minister of the Supreme Court Alexandre de Moraes (who was Minister of Justice under Vice President Michel Temer, the one who assumed the Presidency after the parliamentary coup that ousted Dilma Rousseff in 2016) is adopting more assertive measures. He ordered the dissolution of the encampments, the arrest of their participants and the stopping and impounding of the buses carry them. More than a thousand people were then arrested. Finally, Moraes removed the governor of the federal district from his post and ordered the arrest of the Secretary of Security of the Federal District (a former Bolsonaro Minister), who by then was already in Orlando, together with Bolsonaro.

And how did the Brazilian working class react? The next day, on January 9, they took to the streets en masse, especially in the large Brazilian cities (in São Paulo it was estimated that 70,000 people hit the streets in a demonstration), realizing the need to maintain a government with which the workers can at least maintain some degree of dialogue. More radical figures, mainly from the platform workers, have been gaining more space, going beyond the abstract defense of political institutions and defending the need to adopt all necessary means to avoid the coup against Lula and the working class.

If the main battle cry was “no amnesty,” it was also about the need to employ against the enemy the method they themselves had chosen. The idea that “hope will conquer fear” (Lula’s 2022 presidential campaign slogan), that love will conquer hate, that flowers will defeat cannons (as a famous Brazilian song intones), fell apart in the heavy air breathed by the working masses. As one of the speakers at the march in São Paulo said, “It is time for fear to change sides.” Yes, we add, it’s time for the resistance to turn into an offensive; it’s time to support the progressive measures of the government. Not only that; it’s time to demand more from Lula, time to obligate Lula to use the legalist State forces, with the support of mass movements, against the neo-fascist insurrection in progress; it’s time to demand labor rights for all, time to demand the reduction of the workday; it is time to make the bourgeoisie feel the offensive of the working class; it is time to require Lula to act in a manner equal to the historical moment, thus ensuring his hold on power. If the correlation of forces is unfavorable, it is necessary to say, as the great leader of the platform and intellectual workers Paulo Galo, who started a huge protest against Uber, has said, “The impossible is impossible until it happens.”

It is time, it is true, for indignation and boldness, but it is also time for the left to, on the one hand, stop confusing reality with its desires and, on the other hand, to abandon the politics of the ostrich, taking the head out of the sand and ceasing to think that by not dealing with the problems they will disappear. Therefore, the first step is to acknowledge that the overall conjuncture is adverse and the moment is unfavorable. The commanders of the three branches of the armed forces are still holding to an eloquent silence, without even saying a word to condemn the January 8 attacks. Lula, who has lost the momentum he could have achieved by firing everyone and summoning popular support for the government, has touched only a few high-ranking military officials and has called a meeting in which he offered them contracts and additional state money to “modernize the armed forces,” which was certainly put forth in exchange for the stability of the Government. Again, conciliation from above… Also, in a sign of desperation, he asked for an image of Jesus Christ on the cross that used to be in the Palace during his first Presidency.

Thus, we have a government that begins absolutely weakened, and is hostage to the armed sectors of the state. It is a government that has demonstrated that it has no control whatsoever over this sector, and that, with the exception of army chief Julio Cesar de Arruda, has not fired or at least retired the military of the high command into the reserve (something that Gustavo Petro, in Colombia, did on the first day of his administration).

Political origins, and class positions of Lula and Bolsonaro

Both Bolsonaro and Lula emerged into politics in the 1980s.

Lula is a representative of what was called in the 1970s the “new unionism,” new because the unions would no longer be tied to the State, as part of the previous unions were (a legacy of Getúlio Vargas’s government). The “new unionism” also earned that name because, after the labor movement having been repressed with force and prisons during the military dictatorship (1964-85), the metalworkers unions were then carrying out the first big strikes in the final stage of the dictatorship, in the automobile factories in São Bernardo and its environs (although we must recall the courageous strikes in Contagem and Osasco in 1968). Thus, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Lula led massive strikes, looking to increase wages, which made the basis of the dictatorship tremble. Although from this experience he would later decide that he and the working class should struggle mainly inside the institutions, through the formation of a political party, the Workers Party (PT) in 1980. The PT was founded by union leaders, intellectuals and, another very important element, representatives of the progressive Catholic Church.

On the opposite side, Bolsonaro comes from the extreme right of the military, from the sector that did not want to relinquish power as the dictatorship was coming to an end in the 1980s. En passant, we must remember that the Brazilian dictatorship was not really overthrown; rather, it ended only when the military decided to leave in the context of economic crisis, inflation, and increasing foreign debt. They could leave without being punished, since an amnesty law was approved pardoning their acts of torture and murder, while keeping former guerrilla members in jail. The kind of transitional justice created in Argentina was not replicated in Brazil.

How did the horrific figure of Jair Messias Bolsonaro effectively emerge in Brazilian politics? At the beginning, he appeared on the public stage by making wage demands for the military in the 1980s. He then left the army, being sued and almost expelled because he elaborated a plan to blow up the underground of the city of Rio de Janeiro to pressure the State to give the military a raise. These are the facts that initially projected him politically, first, as a councilman and then, from the 1990s until 2018, a federal congressman.

Regarding their ideological and class positons, how do Lula and Bolsonaro present themselves?

I will start with Lula, the representative of the “left.” In fact, when one places Lula and the PT in the left wing, it is necessary to know which left is being considered. It is a pro-capital, statist and, religious left. It is a left that naturalizes capital, that limits itself to proposing a) limited distribution of income, which is nothing more than distributing through the State the surplus value extracted immediately by capital and mediately appropriated by the State; b) an increase in the minimum wage, which reduces surplus value; c) the strengthening of state-owned companies, especially Petrobras; d) the role of the state as an economic conduit; e) the formation of an internal market through increased spending powers, which also implies reduction of unemployment. While such policies surely bother the bourgeoisie, it is necessary, for the Marxist left, to go far beyond them.

The fact is that these problematic characteristics (pro-capitalist, statist, and religious) are concentrated in the figure of Lula. An excellent speaker, he manages to persuade many that the only possible way forward is through class conciliation. He never bets, or ever had bet, on antagonism, on class struggle, on the control of the means of production by the working class. Instead, he speaks, again and again of the need to sit at the table to negotiate and accommodate interests. Nowadays, he is adopting an increasingly paternalistic approach, saying that he wants to “take care of people,” in the tradition of Joâo Goulart or even Vargas. This kind of talk has very demobilizing effects.

It follows logically that the words working class, bourgeoisie, and social classes, are, nowadays, expelled from the vocabulary of Lula and PT. They do speak on behalf of the poor, of the unemployed, but not of the class, dealing only with income and naturalize social classes, value production, surplus value, money, the State etc.

Nevertheless, in the course of the campaign and even now Lula announced important changes, among them: greater inspection and punishment of deforestation, labor rights to the vast contingent of Brazilian platform workers, the return to the policy of increasing the minimum wage, and the end of the national oil company Petrobras’s current pricing policy of parity with dollar. These are measures that, under more or less normal conditions, could be considered mild reforms. Nevertheless, given the rightist composition of the parliament, the very broad political alliances Lula has undertaken seem to be very big achievements. The alliance includes the rightist Geraldo Alckmin (who disagrees with Lula’s economic policies and has already run in a previous presidential election against him), an alliance that Lula himself called as “Noa Arch,” they seem to be hard-won achievements.

The defeated candidate of the far right, Bolsonaro, supports a state whose functions are limited to the exercise of extreme violence. He wants, as the ultra-liberal that he is, a maximum State in terms of violence, especially against working class Black people, and also against LGBTQIA+ people. But in one aspect he differs from the right that had previously been in government: he defends facilitating access to weapons, but, given the high price of firearms, it is therefore something only for wealthy people, such as the upper middle class, landowners and their supporters, and their militias.

In the economic policy, Bolsonaro postulates minimal state intervention, which he summarizes in statements like the following: “We need to get the state off of the businessman’s neck” and, “People need to choose between having rights and having jobs.” In his Government, he upheld this promise. Here are some examples. Already in his first days in office, the Ministry of Labor, which was an organ of mediation and dialogue between the working class and the State, was extinguished. The labor and environmental inspectors had their powers reduced. He gave broad support to the invasion of Indigenous lands by way of illegal mining. His hateful views on race, gender, and sexual orientation discrimination constituted one of the ideologically cohesive elements of Bolsonarism as a movement. And we must say that Bolsonaro’s Presidency was politically consistent with the hate speech he always propagated, being against affirmative action policies, against teaching sex and gender education in schools, against equal pay for men and women, and in favor of police violence against Black people.

If we could sum it all up in one sentence, we could say that Bolsonaro openly preaches the destruction, in favor of capital and even his own family, of the only two sources of all wealth: nature and human beings.

How did Brazil get to this point, in 2023? Here, a longer historical perspective is needed.

The colonial path of capital’s objectivation

Considering that society is the root of the State, in order to understand, in its broad features, the character of bourgeois society in Brazil, it is important to bring up, as a premise of the Brazilian electoral process, the idea that there are different methods of achieving the accumulation of capital.

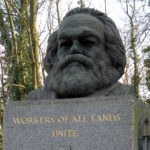

This idea can already be found in Karl Marx, notably, with special clarity, in the Critique of the Gotha Program. In that text (quoted in the recent translation of Kevin B. Anderson and Karel Ludenhoff), just before stating that society is the root of the State, Marx says the following:

“‘Present-day society’ is capitalist society, which exists in all civilized countries, more or less free from medieval admixture, more or less modified by the particular historical development of each country, more or less developed […] more or less capitalistically developed.”

Therefore, we are talking about the particular developments of the capitalist mode of production in different countries and regions. We should also recall that, for Marx, true capital is the industrial capital, because it establishes systematically the method of relative surplus value production and of reproduction.

Starting from the non-exhaustive classification made by the Brazilian J. Chasin, we can find, first, a classical, revolutionary path, as seen in England, for example, with its industrial revolution in the last third of the 18th century. After that we have what Lenin named the Prussian path, a non-revolutionary path, marked by conciliation from above, which occurs in countries that industrialized on a large scale in the last third of the 19th century, having arrived late in the race for colonies and seeking to compensate for it by way of success in reaching an imperialist configuration. This is the case for countries like Germany and Italy, and also Japan. We have, finally, what Chasin called the colonial path of realization of capital, in countries like Brazil, that have a hyper-late industrialization, from the 1930s onward, and that have never reached (nor will reach) an imperialist configuration or even an autonomous national capitalism. It is a path commanded by an essentially atrophic and subordinated bourgeoisie, a bourgeoisie that does not complete its historical tasks and in certain times even struggles against the State to maintain itself in a position subordinated to imperialism.

The political inheritance of the colonial’s path

The heritage of the colonial form of the realization of capital still and decisively guides the current political situation. In a brief outline, there are three fundamental aspects of this inheritance.

The first one is related to the way that the slave mode of production ended in Brazil. There were huge struggles, from the enslaved people and the abolitionist movement, to put an end to slavery and simultaneously enact land reform. Nevertheless, slavery was abolished in 1888; the Monarchy, now without its economic basis, ended in 1889; and the era of generalized wage-labor started without a land reform. As a result, the enslaved people and their descendants, Black people kidnapped in the African slave trade ever since the 16th century, left the farms, the plantations and other sites. But they left without land and jobs, having to make the way for themselves in the informal labor, and forming, since then, the country’s first industrial reserve army.

Secondly, the fact that the state encouraged the immigration of European working people to occupy more formal jobs, along with the positions formerly occupied by the enslaved people, also contributed to the consolidation of this specific social inscription of Black people in Brazilian society. These constitute the roots of Brazilian structural racism, which is an essential element of the capitalist mode of production in this land.

Third, intertwined with the structural racism is the character of the hyper-late industrialization led by President Getúlio Vargas from the 1930s on, a characteristic that still guides the Brazilian political process. And what are the specifics of this legacy?

Put very briefly, we can say that these are fundamentally two:

1) The implementation and maintenance of labor rights, with an emphasis on the institution of the minimum wage, with a policy of constantly increasing it above inflation; the creation of the Labor Court and of the Ministry of Labor; the establishment of a general law, a consolidation of labor laws, in order to limit the power of capital to exploit labor. Vargas, who was a convinced anti-communist (recall that after a failed communist insurrection in 1935 he deported Olga Benario, a participant in the insurrection and wife of Communist Party leader Luis Carlos Prestes; she died in Auschwitz) was in favor of labor rights for two reasons:

- a) he thought it was better to make political concessions from above than to concede to pressure from below, including for the purpose of weakening the communists; in fact, a politician who participated in the movement that brought Vargas to power said the following: “Let’s make the revolution before the people make it”;

- b) to boost the domestic market by increasing the purchasing power of wages, even if this implied a reduction of profit, or, better, of capital’s rate of surplus value.

2) The role of the State as a catalyst in the attempt to develop a dreamed-of autonomous national capitalism through state-owned companies that would operate in the infrastructure areas, commanding strategic sectors for the country’s industrialization. In that respect, the Brazilian national oil company Petrobras plays a historic key role right up until today.

These were the main general trends that guided the republican political process in Brazil. This is proven by some specific points that I will now recall. One of Vargas’s last acts as President was a big increase in the minimum wage signed by his Minister of Labor, João Goulart, in 1954. The military (which since then has played the role of protecting the interests of the atrophied Brazilian bourgeoisie, and of imperialism, by fighting against internal enemies) then tried a coup, whereupon Vargas committed suicide in order to prevent the military from seizing power, therefore delaying the military coup for 10 years. Vargas in his suicide letter also mentioned foreign greed for Brazilian oil and the campaigns against the newly created Petrobras.

João Goulart served as President from 1961 to 1964. One of last acts was to raise the minimum wage and to announce the nationalization of foreign oil refining companies. Shortly after, with support from the United States, the military coup occurred, opposing a popular Government and the project to implement the “Reformas de Base” [Fundamental Reforms] (land reform, tax reform, urban reform, educational reform etc.).

As regards more recent events, it is not an accident that the neoliberal President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2003) used to say, as President, that the main objective of his government was to liquidate the legacy of Getúlio Vargas. What did he mean? To end the protection of labor by the State, to attack labor rights, and to privatize state companies. If Cardoso started this process, the person who accelerated it was Michel Temer, who took over as President after the 2016 parliamentary coup against Dilma, and then Bolsonaro, who is the full realization, in terms of economic policy, of Cardoso’s views. Thus, it is more accurate to say that the legacy that Bolsonaro was trying to exterminate was not exactly that of Lula, but that of Vargas, then represented by Lula and Dilma.

It was no accident that the economic policies of Lula and Dilma, even with their specificities and oscillations (such as Dilma’s neoliberal reaction to the economic crisis arising from the end of the Chinese commodities boom in the 2013s onward) also rest on the foundations of the specific mode of Brazilian industrialization of the 1930s. Their governments had a basic policy of increasing the minimum wage above inflation and of developing Petrobras, especially with the discovery of immense oil reserves in the so-called pre-salt, in deep waters, here using national technology.

The economic crises that resulted from the end of the Chinese commodities boom (that affected all the governments of the so called Pink Tide in South America) led to the “Car Wash” “anti-corruption” operation, commanded by the far-right Judge Sérgio Moro (Bolsonaro’s future Minister of Justice) and far-right prosecutors, with connections with the US State Department. What did this operation do? It promoted lawfare against the Dilma government based on corruption allegations connected to Petrobras and to Brazilian companies, notably in the civil construction sector, that benefited from government economic policies that made them more competitive abroad.

This process, together with other factors — like mainstream media support of the coup, the formation and strengthening of far-right organizations, the abstract support of “constitutional” institutions by the left and the absence of a positive counter-agenda by the working class — led to the parliamentary coup that ousted Dilma in 2016. Then, as it is widely known, that same Judge Moro arrested Lula, preventing him from participating in the 2018 electoral process, and would then become Minister of Justice of candidate Jair Bolsonaro after the election.

That said, it is nevertheless possible that Lula, perhaps realizing the urgent need for economic change and of governing with the people in the streets, as a reaction to the present juncture, has publicly proposed: a) income tax exemption for those in the poorer classes who earn up to 5000 reais; b) return to the policy of increasing the minimum wage ahead of inflation; and c) labor rights for app/platform workers, even calling on them (which is an important modification of his usually paternalistic speech) to pressure the state institutions from outside.

What do we learn from this historical sketch and what does it mean for today? It leads me to the following conclusion.

We must demand the investigation and arrest of the coup perpetrators, their political supporters (starting with Bolsonaro and his family), and their financial backers. But it must be understood that this is an organized neofascist attack that is not over yet and will not be defeated only by the action of legal and state institutions. It needs to be defeated in the streets, by the union of all sectors of the working class, which needs to be organized, thus creating pressure from outside the state. That pressure needs to come, whether the government wants it or not, using against the fascist enemy all necessary means, and employing legitimate defense based on the method already chosen by the workers’ enemies: force.

REFERENCES

Brazilian Elections 2022: Challenges and Space of The Resistance of The Brazilian Left

LEAVE A REPLY

2 Comments

LEAVE A REPLY

2 Comments

Sam Friedman on February 13, 2023 at 7:29 am

Sam Friedman on February 13, 2023 at 7:29 amThis is a really excellent and informative article. I would urge the author to write a follow-up on the organizational and consciousness of the negation of the power structure he describes here–that is, of workers, Black, LGBTQIA+ people, the left, and others.

Rodrigo on February 24, 2023 at 1:13 pm

Rodrigo on February 24, 2023 at 1:13 pmThank you, Sam. As – and if – this negation of power and capital develops, I´ll be glad to do it comrade!

This is a really excellent and informative article. I would urge the author to write a follow-up on the organizational and consciousness of the negation of the power structure he describes here–that is, of workers, Black, LGBTQIA+ people, the left, and others.

Thank you, Sam. As – and if – this negation of power and capital develops, I´ll be glad to do it comrade!